|

| Nursing Students in front of N-6 building |

|

| The By-Line Newsletter, April 1950 |

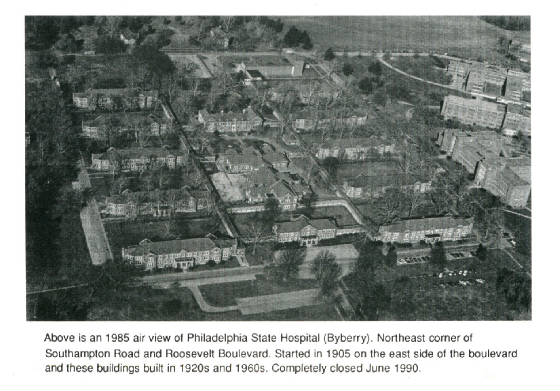

By the late 1950's, Byberry stood with 58 buildings, 0ver 6500 patients, and just over 1000 fully equipped staff members and

doctors, but still unsatisfactory numbers of "rehabilitated". A new Occupational Therapy department was formed.

This offered patients the chance to learn a new hobby or skill, or just a chance to get out of the dayroom. In the 1950's

the area grew rapidly. The pre-fab homes on the new streets to the west of Byberry were built for staff members. They sold

for between $4,000 and $7,500. The area was beginning to see progress as the new roads, houses and schools reached out towards

Byberry, but the houses in the immediate area were built for workers and their families.

A change that occured due to state control in the 1950's was a redesignation of building titles. The north group

was split into the north and west groups. N-3, 5, 6, and 7 were changed to W-3, 5, 6, and 7. The female buildings were now

classified as the C buildings or central group, as they were located between the South and North groups. The east group, or

the male side, were now called the E buildings. The south group, mostly built for staff, were now called the S buildings.

Partially responsible, at least financially, for Byberry's turn-around was Furey Ellis. Ellis was the on the board of

Prisons. He was a big advocate for prisoners' rights, having exposed the deadly "Klondike Cells" at Holmesburg Prison.

Ellis became chairman of the board of trustees for Byberry in the 40's and into the 50's. He fought for funding and improved

the way money was spent at Byberry, opening up new areas of progress. In 1955, a new auditorium was constructed and named

for the man who raised the money to build it.

Equipped with modern film projectors and accomodations for up to 400 patients, Furey Ellis Hall improved public relations.

A new stretch of hallway was built connecting the auditorium to the rest of the hospital with one wall being made of 4 inch

thick glass, definately moving away from the 'hospital' look.

| C-9 building, circa 1985 |

|

The children's camp was renovated into chapels in 1966. One was a Protestant Chapel, another a Synagogue, and cottage 1 became

"John F. Kennedy Hall", the catholic chapel for the hospital. The children were transferred to C-4 and C-5.

The 1960's also brought about a serious rise in transportation issues as well. The rise of the autombile allowed the hospital

the use of the staff buildings as patient dorms. By the mid 1970's, the S buildings, or south group, were no longer needed

as hardly any staff chose to live there. The recreation section was the only part still in use until downsizing forced it

too to close. The south unit was demolished in the late 1970's, and by 1980 a new industrial park was in operation on the

site. In turn, W-7 had been re-designated "south unit". It was bricked off from the connecting tunnels and became

used for the small amount of remaining staff who still chose the option to live on the grounds, as well as staff offices and

makeshift lounges for staff and visitors.

President Kennedy's call for deinstitutionalization officially began in 1963, and small, community-based mental health

centers were built around the country. This marked the beginning of the end for Byberry and other big institutions like it.

The rise of psyciatry and advances in psycho-theraputic drugs achieved more progress in ten years than any state or private

mental hospital had in two hundred. The spread of thorazine was almost worldwide by the 1960's. The state turned its funding

almost 180 degrees from Byberry's direction, and right to private and corporate mental health centers. Byberry began its downsizing

process in 1962, releasing almost 2000 patients to mental health centers, other hospitals, and the streets of Philadelphia

between 1962 and 1972.

Byberry staff was now forced to downsize the hospital rapidly, and work against a decreasing budget to find homes for

it's remaining patients. The E buildings, which had begun the transfer of its patients to the north and west groups in 1954,

were completely closed off by 1967. By the mid 1970s, funds had dropped so significantly, the hospital was forced to stop

accepting admissions and had begun the transfer of its patients to other facilities. In the early 1980's, administration was

moved to W-3 building, and the C buildings became mostly vacant. In 1985, N-8 received a thorough interior makeover and was

used for as the forensics unit. N-8 held Byberry's most violent and dangerous patients between 1985 and 1990.

| W-3 building, circa 1985 |

|

Within ten years, the almost immediate release of thousands of psychotic and schizophrenic patients by the state after receiving

thorazine was already proving a hurried and ultimately damaging decision. In 1982, an investigation of Byberry's credentials

by a Medicare official forced another debilitating blow. According to federal requirements, Byberry was understaffed by 75

nurses and in order to remain a hospital that accepted Medicare, Byberry was given a choice of either discharging about 300

patients, or hiring 75 nurses to comply with the federal law... within 90 days!

The staff that remained at this time were mostly loyal, honest doctors who truly cared about the well being of their patients.

Unfortunately, these doctors were faced with a true moral dilemma. The option of hiring 75 nurses in three months was more

or less impossible given popular opinion of the hospital. The head of each unit received a memo from the superintendent with

instructions to prepare a specified number of patients, varying by unit, for immediate release. About half of the patients

were moved to nursing homes and other hospitals, but more than 120 patients were released onto the streets of Philadelphia.

Transfers occurred for the more serious and dangerous patients released, and most of those released to the streets were senile,

or feeble-minded patients who had been at byberry for decades, some for most of their conscious lives.

Some staff reported patients in tears, pleading to stay. But all throughout the state, it became harder and harder for

mental hospitals to function. Most of them got around the Medicare problem with unit re-designations, shifts in patients within

the physical plants, and releasing and transferring patients. Throughout Pennsylvania, needless to say, Philadelphia saw the

highest number of improperly discharged patients wandering it's streets, homeless and lost, often committing suicide or ending

up in prison. Byberry had stopped accepting admissions and dozens of former patients remained wandering the grounds and in

some cases, gaining entry and turning up back on their former wards. But byberry continued discharging and releasing patients,

and naturally, staff along with them.

The number of dedicated and experienced staff members left at Byberry was dwindling. The state and medical field had just

about given up on Byberry by now. Countless unresolved homicides and disappearances of patients kept the horror on the front

page of Philadelphia's newspapers. An unfortunate man named William Kirsch was finally let out of restraints after three years.

Muscles atrophied, he needed physical therapy at 27 years old.

March 9 1987/PRNewswire: William Kirsch, a 27-year-old person who has

been shackled in four-point restraint at Byberry State Hospital for the past three years, today was declared to have his

constitutional rights violated. James Kelly of the U.S. District Court for Eastern Pennsylvania ruled that Kirsch had been

"deprived of his rights under the due process clause of the Untied States Constitution." His attorneys, Stephen

Gold and Ed Tiryak, said the decision "confirms an important Constitutional right." The judge ruled that Kirsch's

condition "deteriorated during his years at the Philadelphia State Hospital", and the "environment and programs

at Byberry have caused regression and intensified Mr. Kirsch's assaultive behavior." The court further found that Kirsch

suffered numerous physical injuries and several broken bones since January 1987.

| W-7 Building, circa 1985 |

|

In Febuary 1987, a patient froze to death on the grounds of Byberry. He simply wasn't able to find anyone to let him inside

after easlily escaping. Residents of Carter road and the neighboring houses, were commonly finding patients sleeping on their

lawn, and sometimes, in their homes.

In June of 1987, with 40 patients still on the forensic ward (N-8, 2A), a particularly grizzly event took place. A young female

patient was raped, murdered and easily disposed of on the property by another patient. For the next two months her decaying

body was the entertainment of other patients. One patient apparently enjoyed showing off a few of her teeth to other patients

on the ward. By the time the staff located her, it was almost 9 weeks after her death. In 1989, the remains of two more patients

were found while clearing out the high grass and weeds that had accumulated on parts of the property. One had been missing

almost 5 months. There was also an issue with dead patients around the area that had gotten out and commited suicide. And

then there's Anna's story.

Anna Caroline Jennings was an unfortunate young woman who spent most of her life going from one mental hospital to another.

A talented artist, she suffered from post traumatic stress disorder. In 1982 she was transferred to Byberry. Her stay at Byberry

was both a blessing and a curse. During her time at Byberry, Anna was repeatedly raped and sexually abused by staff members

and other patients. She tried repeatedly to tell other staff what was happening, but apparently no one intervened. Anna told

her mother about the abuse and her mother tried unsuccessfully to stop it. Anna received a special form of treatment at Byberry

that was able to target the cause of her mental illness, early childhood sexual abuse. Anna was making progress and the doctors

at Byberry were working on a regiment for her when state budget cuts forced the program to stop. Anna quickly fell back into

her self-destructive behaviors and commited suicide in 1988. A website devoted to her can be found here:

http://www.theannainstitute.org

The last nail in the coffin was hammered in 1987 when governor Bob Casey had the hospital thoroughly searched and observed,

turning up conditions that made headlines around the country. Casey ordered the hospital closed in phases, closing each building

until there were but five patients left.

Oct. 1989: Of the patients at the hospital at the time of

the closure announcement: 40 moved to the forensic unit at Norristown State Hospital; 77 were discharged to nursing beds;

153 were transferred to Norristown State Hospital; one was transferred to Harrisburg State Hospital; 276 were discharged to

community-based mental health programs; and 23 have died.

White said that patients were individually evaluated and placed

in programs that best met their needs.

The hospital's 140 current employees will transfer, retire, resign or be furloughed

by June 30, with the exception of 14 staffers needed to complete the final phase of the shutdown. Those staff members will

secure the grounds, weatherize buildings, store furniture, complete records and otherwise maintain the facility.

|

| A pictorial glimpse into the past 2, Pat W. Stopper |

In 1990, a team of 17 willing staff members carried out furniture and other important items, believing the hospital was to

be standing for but a few months more. The last building to close was N-8, which contained the last five patients. They were

released in June of 1990. But in just a month, four of the five ex-patients were found dead in the Schulkyll river. Staff

at the hospital held a candlelight vigil for these four patients, and had there names posted up on the main gatehouses. The

Daily News printed an article about Philadelphia's increased percentage of homeless. It cited the closing of Byberry as a

major contributing factor. Opinions shifted and people thought maybe Byberry shouldn't close.

The type of patients at Byberry were in need of real care, not outpatient privatized therapy. All in all, Byberry transferred

about 79% of it's patients to other "acceptable" facilities. But over 2500 patients were let out into the streets.

They were each given 25 dollars, one pack of bus tokens, and an appointment at the outpatient clinic. Some ended up commiting

violent crimes and were locked away in other facilities. Some died from overdoses, some from suicide. Others came back to

the only place they really felt safe, their now shuttered former home, Byberry.

| Building C, or E-6, "the Rosegarden", circa 1989 |

|

| Photo by Jim Bostick |

Demolition started with the E buildings in 1991. Most of their materials such as the mass amounts of copper had long since

been looted. They had been the victim of countless fires and vandalism as well. Having been abandoned since the 1960's, they

were but shells of former glory. One building from the east group was salvaged and refurbished, E-6. It still stands today

as a business. The rest of the E buildings went down quickly with few problems. Most of the asbestos had been removed by scrappers

to get at the pipes, and proved easy to dispose of.

But when demolition began on the west group, unsavory amounts of deadly airborne asbestos was discovered in every building.

The state calculated it's removal at a cost of 13-16 million dollars (not including demolition), and decided to leave the

buildings alone and hired a security company to watch its grounds. After an alleged overdose victim was found inside, every

one of thousands of windows and doors were boarded up at an estimated cost of about 100,000 dollars, and the hospital remained

in solitude.

All in all, Byberry was a "bottomless money pit" to the city and state. Although intentions were always good,

much of Byberry's features were highly overlooked. It has always been looked at as a "dumpy" place. A place to send

grandma when the family no longer wanted to deal with her. Despite the strong efforts by its staff and doctors, Byberry's

reputation stood as a place where no one wanted to be. Poor Byberry was just as much a helpless victim as its patients, of

misunderstanding....

| East campus Administration, or E-1, circa 1989 |

|

| Photo by Jim Bostick |

|