|

In 1675, the area known today as Byberry, in the northeast section of Philadelphia, was settled by four brothers, the

Waltons and their families in an attempt to establish an area in which to freely practice their Quaker religion. They named

this area after the name of the town in England which they came from, Bibury, near Bristol. Although the area was not yet

officially founded by William Penn, the Waltons knew it would be great place to settle.

The Waltons were followed some years later by the Knights, the Carvers, the Comlys, and my ancestors, the Gilberts of

Cornwall. John Gilbert arrived on the ship "Welcome" with William Penn in 1682. The byberry area was then known

as Smithville. It was rich with farmland and was very habitable next to the Poquessing creek. Many Lenni Lenape indian artifacts

have been discovered in this area. Dr. Benjamin Rush was born in Byberry in 1746. His signature on the declaration of independence

as well as his work at the Pennsylvania Hospital with the mentally ill and countless other ailments, have earned him the title

"father of American Psychiatry". His birth home was less than a mile from where PSH was erected. An informative

book about Byberry in the early days of America called "the history of the townships of byberry and moreland" by

Joseph Martindale is available on Google Books.

The Byberry area throughout the 18th and 19th centuries consisted of mostly farmland. There was a large Quaker population.

There were also Baptists, Anglicans, and Unitarians. There was a powerful underground railroad in Byberry too. It was the

home of Robert Purvis, staunt abolitionist who built Byberry Hall in 1846, and frequently held anti-slavery meetings there.

It still stands next to Byberry Friends Meeting house.

Not until the mid 19th century did most of what is now northeast Philadelphia become somewhat densely populated. Endless

farmland and forrest separated the city proper from Byberry. The railroads brought the first easy access to this part of the

city in the 1860's.

The Consolidation Act of 1854, which brought Philadelphia from 8 square miles in size (the Delaware river to the east,

Schuylkill river to the west, Vine [originally North] street to the north, and South street to the south), to it's current

size of 135 square miles by combining city and county, almost didn't include Byberry. The farmers who lived there did not

want to pay city taxes and enjoyed small "town tax" rates. They knew what would happen as a result of being absorbed

by the rapidly-growing city, and they were right. But as history would have it, this was the northernmost township the city

would cover, making it the perfect location for a mental hospital.

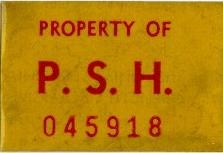

| The Grubb Farmhouse, circa 1911 |

|

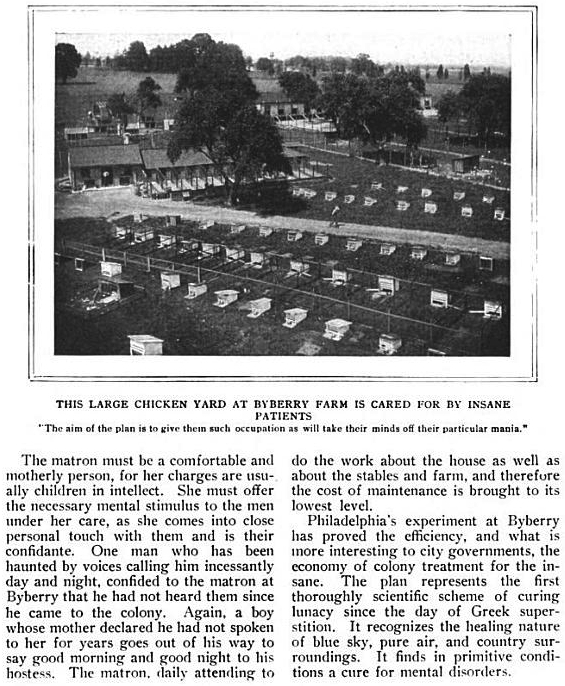

| Google Books, Technical World Magazine, Farm Treatment for the Insane, 1911, p. 582 |

In 1903 the state legislature passed the "Bullitt Bill", which required among other things, that each county erect

at least one facility, depending on population, specifically designed for the care of it's indigent mentally ill (those with

no means to pay). The mentally ill in Philadelphia at this time, depending on social class (i.e. family, or wealth), actually

had some of the best options in the United States. The "Friends Hospital for the Indigent Sick-Poor" was one of

the first hospitals in the country built for the care of the mentally ill, but it was not free. The Pennsylvania Hospital

at 8th and Pine, the first public hospital in the United States, also offered care to mental cases, but also for a price.

Thomas Kirkbride's "Hospital for the Insane" in west Philadelphia, built in 1856, was another option, this one being

the best as it was free and offered decent custodial care. But by the turn of the 20th century, admission to Kirkbride's hospital

had become difficult as it was well filled to capacity.

The Blockley Almshouse (later known as Philadelphia General Hospital) on the west bank of the Schyulkill river (present

site of Children's Hospital) was an insitution built during the quaker "revival" of the 1830s and had become the

city's "dumping ground" for it's unfortunates who had nowhere else to go (homeless, TB sufferers, drunks, as well

as the mentally ill). The buildings were far outdated and inadequate to house the growing population of "inmates".

Meanwhile, the city had been purchasing farmland for it's Holmesburg Prison Farm, an inmate-run farm for the supply of

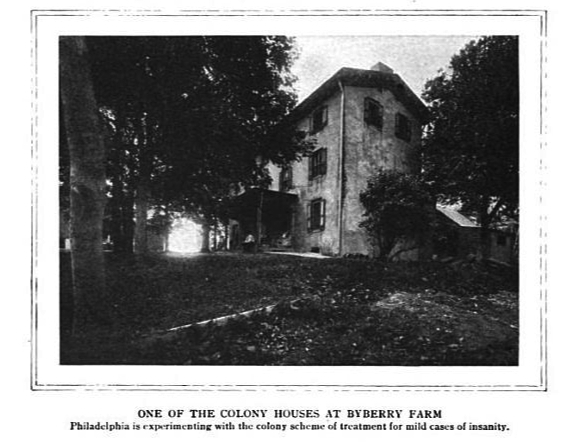

food for all of it's public institutions. It soon became known as "Byberry Farms". The doctors of the insane ward

at Blockley, headed by Chief Physician Jeffrey A. Jackson, experimented at Byberry Farms with what became known as the "colony"

plan. The plan was originally meant for Tuberculosis patients. By transferring Blockley's TB unit out to Byberry, more room

was made there for chronically insane patients. The "experiment" at Byberry yielded excellent results. TB patients

received the fresh air and exercise they needed, and were certainly happier as a result.

During the "reign of Ashbridgism", the mayoral term of Samuel Ashbridge, there were several factors that caused

the new system to spoil. The growing population of the city, the new regulations placed upon the city by the new Bullet Bill,

the aggitative nature of the hospital reform movement, and the eagerness of the Ashbridge administration to get the spotlight

off of its own "rotten innards", ultimately led to the idea of "hiding" the large and increasingly uncontrollable

population of the city's insane out at Byberry.

The city's original plan was to erect the new hospital on land recently purchased from the McCalister family (owner of

the Glen Foerd mansion and adjacent land) just north of the new Torresdale Filter Plant on the city's extreme northeastern

border. This plan however, turned out to be too costly for the city and did not afford the necessary space required to build

a decent facility, not to mention its close proximity to the developed neighborhood of Holmesburg, which contained over 8,000

residents at the time. Holmesburg residents voiced their concerns to the mayor. Already unhappy about the new House of Correction

the city erected in their neighborhood, the citizens of Holmesburg were not about to allow a mental hospital be erected.

The city's surveyors and a committee decided that the Byberry Farms could much more easily be expanded into an area fit

for a mental hospital. The city had no problem acquiring land in byberry by cheaply buying out farmers who'd had it with their

growing city tax rates. The Keigler, Mulligan, Kessler, Jenks, Grub, Tomlinson, Osmund, Carver, Alburger, Updyke, Comly, Carter,

and later Myers/Stevens (1911), and Dyer/Bening (1913) properties made up the hospital's 1500 acres (1000 acres in byberry

plus an additional 500 acres in Bucks County). The total cost of the land was $261,000.

Soon after the land purcahses, six "competent" inmates from the overcrowded insane department at Blockley were

chosen to work at the farms. The population of patients at the farms began to increase in the next few years, as the patients

themselves constructed their own temporary dormitories, slowly relieving the overcrowded, 80 year old Blockley. The city (and

the general public) began to like more and more the idea of sending it's most dangerous citizens as far away as possible.

|

| The old Tubercular building, the Osmund house, with additions by Johnson. Circa 1912 |

The turn of the 20th century marked the beginning of the end for the KirkBride Hospital design plan. Most states had erected

new facilities based on the colony plan. However, Kirkbride's basic principals of care for the insane were still the norm

at most government-run asylums.

Byberry was located 20 miles from the city proper and was the most rural area within the city boundaries. The term "funny

farm" originated from the fact that almost all mental hospitals or asylums had been constructed in the middle of endless

farmland, far away from the cities they served. In 1906 the first director of the DPC, Dr. William Coplin, stated in a report

to then-mayor John Weaver that the byberry tract "is splendidly located, well suited to farming and possesses a surface

contour adapted to the erection of buildings for the reception of the insane at present crowded into the insufficient space

afforded by antiquated buildings long out of date and no longer capable of alteration to meet modern requirements."

By 1906, Byberry Farms consisted of about 15 farmhouses that had come with the land purchases. These were converted to

"colony houses" and the city built several small wooden buildings to house the 150 patients that had been moved

from Blockley. The first patient was fabled to be a man by the name of William McClain, admitted to Blockley for alcoholism

in 1907, and sent to Byberry Farms to work.

|

| Google Books, Technical World Magazine, Farm Treatment for the Insane, 1911, P. 583 |

Philadelphia politics at the turn of the 20th century was overflowing with corruption and graft. The "Republican Machine"

that ran city politics since the before the Civil War had transformed into one of the most powerful and unstoppable forces

in political America. The men that ran the machine made their fortunes in the railroad and transit industries, the huge banking

boom created after the civil war, and the complete monopoly of city projects. It was never hard to get a favor from the city

government as long as you were connected to the machine, and everyone knew it.

America is a country where poor newcomers can truly work their way up from poverty to become powerful politicians, regardless

of social class. However, Philadelphia in the early 20th century was not a good example of that value. Recruitment into the

machine usually required a long family and financial connection. Ultimately, Byberry was one of thousands of products of the

corrupt Philadelphia Republican Machine. It was built for two reasons. First: to confirm to the legislature's request of a

separate facility for mental patients; and second: to return favors for election contributions and perhaps do a few others

in the process. But if there was no legislative DEMAND for byberry, it would not have been built.

It seems sadly, that scandal, corner-cutting, greed, and dishonesty plagued the byberry administration's entire existence.

Right from the beginning, the construction of Byberry was scandalous. It's construction was placed in the hands of Philip

H. Johnson, who was right at home floating in a river of corruption.

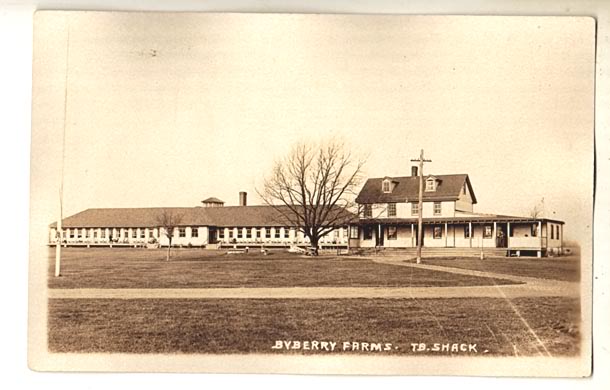

| The superintendent's home, the Myers/Stevens house |

|

| Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Record, circa 1938, V7:2786/.67 |

The Department of Public Welfare was one of three departments carved out of the former "Department of Health and Charities"

as a condition of the Bullet Bill signed in 1903. The Department of Public Welfare was to control the state's public hospitals.

Israel Wilson Durham, boss of Philadelphia's 7th ward, had grown into the single powerhouse that controlled Philadelphia by

1900, very similar to Enoch "Nucky" Thompson of "Boardwalk Empire". In 1891, Durham was elected state

senator and, during his 12 year term, chose every mayor and practically every member of city government; he was the "boss"

in Philadelphia.

Philip H. Johnson of Philadelphia's Dept of engineering, married Durham's youngest sister in 1902 and was thus interred

into the Machine. As his brother-in-law, Durham saw to it that Johnson was taken care of. He gave Johnson the position of

Architect for the Dept of Public Welfare..... for the rest of his life! Johnson was a perfect choice for the Republican Machine.

He had no problem taking payoffs from contractors or using cheap, out-of-contract building materials and labor to cut costs.

His blatant acceptance of payoffs during his position of supervising architect of the construction of city hall made national

headlines. The construction of Philadelphia city hall ended up costing the city more than five times the original estimate.

The city treasurer received bills such as five hundred dollars for a doorknob, or two hundred for a light fixture. The corruption

was immense but as the Republican Machine's official architect, Johnson was untouchable.

In 1902,"Is" Durham chose John Weaver as Mayor. Weaver and Durham had been longtime friends and business partners,

and Durham was sure he could puppet Weaver as he had done other mayors for 20 years. But in 1904, Weaver turned on Durham

and exposed his corruption and history. After a bitter legal fight, Weaver succeeded in expelling Durham from politics. Durham

moved to his summer home in Atlantic City for the last 4 years of his life. He died in 1909 during a luncheon and was buried

at Mount Moriah Cemetery. But even after Durham's death, Johnson held onto his power.

The Weaver administration tried unsuccessfully to oust Johnson from his position. The courts held up his contract as unbreakable

and Johnson became somewhat of a "bully" to most architectural and construction firms in the region. His unflattering

obituary in TIME magazine spoke, perhaps for the first time, of how Johnson's title of Department of Public Welfare Architect

was "in perpetuity", and how Johnson's deal with the city allowed him to collect six percent of final construction

costs as a separate commission. During his career, he became known as the stiff wheel in Philadelphia architectural politics,

and more firms grew to accept the idea that they basically had to pay Johnson to un-involve himself from their project. He

became more and more a politician and less an architect. However, he is credited with designing the Philadelphia General Hospital

additions to Blockley, the City Hall Annex, the Philadelphia Convention Center (now demolished), the Eastern Pennsylvania

Institution for Feeble Minded and Epileptic (Pennhurst State School) in Spring City, which opened it's doors in 1908, and

the Pennsylvania Homeopathic Hospital (Allentown State Hospital).

In 1915, the city's new mayor, J. Hampton Moore, frustrated by Johnson's stranglehold, hired another architect to design

the female buildings at Byberry. Johnson not only sued the city but made them pay his legal fees out of his newly awarded

commission. Moore hired a team of architects to "probe" into Johnson's career and architectural training. They turned

up a muddled past. No proof could be found that Johnson had had any real architectural training at all. An article in the

Public Ledger reports that mayor Moore then hired architect John P. B. Sinkler as the new "city architect", breaking

Johnson's contract. But according to the PA supreme court, without Johnson's approval, nothing Sinkler designed could legally

be built by the city. Moore got around this by hiring Sinkler and other architects to "obtrusively alter" Johnson's

existing buildings. In some cases, as with one building at Philadelphia Hospital for Contgeous Diseases, another of Johnson's

projects, the city payed Johnson his fee for designing an inferior building, then payed another architect to alter the building

to the point that it was practically a different structure. It was suggested that Sinkler actually designed many of Johnson's

projects, but because of Johnson's "perpetual" contract, he ended up receiving the actual credit. There is no proof

of this of course.

The Machine re-took control of the city after Moore's term was up, and the days of reform were again brought to a halt,

for now. The new administration bore with Johnson's (or Sinkler's?) apparently now unpopular cottage plan. By the time of

Johnson's death by heart failure at age 65 in 1933, he had accomodated $1,799,211 in commissions alone. His death was surely

a relief even to the corrupt city of Philadelphia... and Byberry was probably Johnson's most unmanaged and payoff-ridden project.

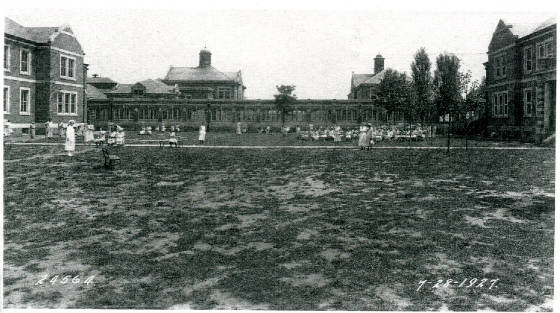

| Official city photo of the east (male) campus |

|

| City of Philadelphia, Dept. of Records, Charles L. Howell, August 1927, Public Works 24582-0- |

Although the layout of the campus had already been planned by the architect, contruction was a slow process. Six dormitory

buildings, an infirmary, a laundry building, an administrative building, and a combination kitchen/dining hall and power plant

(how sanitary), were to make up the east group. or male group. However, it was not fully completed until the mid 1920's. The

first building officially constructed by the city was the east power plant/dining hall, the centerpiece of the east campus,

in 1907. It was was followed by buildings A and C in 1909 and 1910, respectively, and buildings B and D were completed by

1912.

Connected by dark, already leaky and often puddley underground patient traffic tunnels, the buildings were reminiscent

of a nazi concentration camp. They held the "incurable" males of Philadelphia, only the "acute" cases

remained at Blockley. In 1917, the military considered renting Byberry from the city to use as a hospital for soldiers in

the "Great War". The city was more than happy to oblige. But once an officer from the war department visited Byberry,

he quickly rescinded the offer. Byberry immediately began it's reputation as a last resort warehouse for chronically ill patients

whose violent behavior had continuously landed them, transfer after transfer, at other hospitals in the commonwealth that

were unable to contain them.

The west group would consist of sixteen buildings; Ten identical dormitory buildings, a dining hall/refectory building,

two buildings for tubercular patients, a laundry building, an administrative building, and an infirmary. Construction began

in 1913. These buildings were a bit more architecturally ornate, having the connecting hallways above ground with large illuminating

windows, perhaps a sign of the city's recognition of it's shoddy construction on the east group. The first of which to be

built was the dining hall/refectory, followed by C-4 and C-10 in 1915-1916. The first World War called a halt to further construction

until 1919, when work began on the west power plant, this time built a distance from the campus it served. It was completed

in 1921.

Buildings E through J in the east group were completed by 1926, and the remainder of the west group was finished by 1927.

The last building of the west group to be constructed was the Infirmary (C-14), which was not added until 1935, under already

dire criticism of the hospital's condition. It showcased an Otis elevator, medical/surgical rooms, laboratories, dental equipment,

a medical textbook library, and a bed capacity of 70.

| Official city photo of the west (Female) campus |

|

| City of Philadelphia, Dept. of Records, Charles L. Howell, Public Works 24564-0- |

In May of 1928, the campus was just about completed, and it opened officially as an independent, city-run hospital, no longer

an arm of Blockley. The "Philadelphia Hospital for Mental Diseases" was now Byberry's official moniker. But by 1930

the buildings, some less than 10 years old, needed almost constant repairs. The patients found it easier and easier to escape

the property as more and more staff and attendants quit. One patient "chewed his way threw a wooden window frame"

and escaped. Another easily used a "spoon from the kitchen to open a locked door". The first world war had brought

to byberry waves of returning servicemen with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or "shell-shock", and byberry

was forced to carry the increasing load. It wasn't long before the situation became literally out of control.

In a desperate attempt to hire attendants, a sign was erected outside the property which returned a large "group

of transients", but "if they wanted the job, they got it." This resulted in byberry's first public outcry.

In 1919, two male attendants were arrested for murdering a male patient. Another staff member testified that one attendant

held the patient down while the other "choked him till' his eyes popped out". It was learned that both men had just

returned from the war themselves and were probably suffering from PTSD. Charges were dropped and both men were re-hired at

higher pay rate.

Expansion of the hospital called for a separate unit for children. The children's group began construction in 1926. Located

on the southwest corner of southampton road and Roosevelt boulevard, a group of six cottages, a cafeteria, a small administrative

building, and a small playground were hastily constructed to house children. The cottages were complete and in use by 1927.

| Official city photo of children's ward, Cottage 4 |

|

| City of Philadelphia, Dept. of Records, Charles L. Howell, August 1927, Public Works 24581-0- |

After only two decades, Byberry's 19th century methods were fading fast, washed away by the flood of overcrowding and new

unfamiliar ailments and challenges. The buildings themselves, built for a total population of 1000 male, 1000 female, and

100 children, were being bullied and abused by numbers in the 4000's. President Roosevelt's WPA (works progress administration)

was able to band-aid the problem a bit with maintenance and building improvements, but Byberry was still in big trouble. Unfortunately,

the people who bore most of this burden were the patients. As Byberry grew in population, the paid staff at the children's

camp were transferred to the male group. A small number of more responsible male patients were put in charge of the children's

camp.

The stigma of the mental hospital was scary to the general public, and for good reason. Needless to say, Byberry was not

the place to be during the depression years. Although undocumented and ultimately forgotton, these were Byberry's most horrific

years. Chances are, the stories that circulated about nude patients, gaping roof leaks, rats in the food and bed shackles

for weeks at a time, were sad, everyday realities at this time.

Allegedly, the hospital was given so little money by the city during the depression that after patients had destroyed

their clothing, they were housed in designated buildings where patients were naked all year round simply because there were

no clothes or shoes for them. The city hired drunks and pretty much anyone off the street who was willing to work for the

measley wages they offered. Often after being arrested on a minor charge, petty criminals were offered the choice of jail

or work at Byberry.

| The nearly completed West Campus in 1935 |

|

| City of Philadelphia, Dept. of Records, William A. Gee, December 1935, Public Works 35462-0- |

The staff at byberry ranged from the generic attendant, to the pampered superintendent. In between there were doctors, nurses,

pharmacists, lab workers, stenographers, clerks, maintenance workers, groundskeepers, and 2 firefighters. In order to work

at byberry, living on the grounds was required, as there was many miles between the hospital and any populated area where

houses were in Philadelphia at that time.

In the 1920's, before any buildings were built to house staff, the attendants slept in the attics of the dormitory buildings.

The old farmhouses that came with the city's purchases of land were all utilized for a purpose, mostly to house staff prior

to the completion of the staff buildings. An example of guilded-age social class is seen in the not un-costly, separation

of the employees' living quarters according to pay scale. For example the city used the former Carver house, an early 19th

century dwelling, for the housing of it's male attendants- the employees with the most patient contact, and probably byberry's

most important, although consequently, the lowest paid.

By adding two frame wings to either side of the "Carver Cottage", room for more male attendants was made, resulting

in almost the same living conditions as the male patients they were hired to care for. In the late 1920's, a larger building

was erected for the male attendants, followed by the nurses and female attendants quarters in 1930. However, in the mid 1930's,

when the city's financial situation was the worst, they carefully erected a separate (and more expensive) mansion to house

the doctors, clearly showing the importance of social class.

| Home for nurses and female attendants, 1931 |

|

| City of Philadelphia, Dept. of Records, August 1931, Maurice D. Abuhove, Public Works 31643-0- |

Between 1906 and 1912, an older, responsible patient acted as "head farmer" at byberry farms. He was responsible

for the daily farm work, as well as the feeding and order of the patients on the farm, which by 1912, was 264. The first unofficial

superintendent (chief Physician) was Dr. Jeffrey Allen Jackson M.D., previously the director of the insane ward at Blockley.

He was transferred to byberry in 1912, grudgingly, after being refused a position at Warren State Hospital, his desired location.

The recently purchased and refurbished Myers/Stevens house was Jackson's home however, until 1920, when he transferred to

Danville.

Jackson's replacement was Samuel W. Hamilton in his first administrative position. Hamilton lasted only two years before

transferring. Hamilton ended his career as the superintendent of Essex County Overbrook Hospital in Cedar Grove New Jersey

and died in 1951. Hamilton's position was next filled by Everrett S. Barr in 1927. Barr's corruption proved too uncontainable

for the machine to hide. In 1931, Rev. Dr. Harry Burton Boyd, pastor of Arch Street Presbyterian Church, accused then-mayor

Harry Mackey of hiding the truth about byberry from the public. In Boyd's letter to the mayor, he wrote :"No one is interested

in cleaning up this mess. Insane folks do not vote." Calling the patients "victims of political jobbery", Boyd

wrote that "he (Mackey) stated that the helpless insane should not be exploited. He promised to remove the lid. He did-took

one sniff and slammed the lid back on." In response, Mackey hired a team of ten doctors to inspect the hospital "on

paper and on site". Known as the McLean committee, the team did a three month assessment, concluding that the hospital

was 300% overcrowded. The McLean committee wrote up a list of recommendations to improve the hospital's condition, which included

about 1.5 million in repairs. In the long run, all that came to fruition from the committee's report was about $300,000 worth

of repairs, and the rear addition of the nurses residences to accommodate more attendants, and most of the repairs were done

with WPA labor.

Mackey appointed Dr. F. Sands superintendent, replacing Dr. Everett S.Barr after his quick resignation in 1931 following

accusations of a "slush fund". Dr. Sands was able to hold onto the reigns until 1938. when he too retired. Wilbur

P. Rickert, former director at Danville State Hospital, took over after Sands, inheriting byberry at its absolute worst.

In 1936, a Philadelphia Record photographer Mac Parker, disguising himself as an attendant, snuck in his camera

and took some very revealing photos of life inside byberry. His photos forced the public to see what it was like inside the

"snake pit". Rickert resigned after the photos surfaced. The Public Ledger charged him with "irresponsibility".

Ugly stories were mentioned. "The truck used to convey food to the patients is also used for removing the dead..."

was one such story. Another told of the sexual abuse experienced by children at the hands of the "more responsible"

patients that were in charge of the children's camp. Several women patients became pregnant from the same attendant. It was

clear that a drastic change was demanded by the public.

By this time, 40 of the 48 states in the union had state-controlled mental hospitals. In 1938, mayor S. Davis Wilson,

at the end of his term and pushing for a senate seat, finally agreed to sign the dying hospital over to the state and out

of the city's unsteady hands, admitting defeat, but bringing Byberry out of the dungeon. Byberry was about to get an overhaul...

NEXT PAGE

|