|

By the late 1930's, the condition of patients, given overcrowding, understaffing, and lack of treatment of any kind, was so

deplorable that the city was forced to invest state help. Byberry was transferred to state funding which, at the time, is

exactly what it needed. The commonwealth could provide the additional buildings needed to contain the constantly escalating

percentage of overcrowding. The hospital was about 300% overcrowded at this point, fortunately the worst number it would see.

The state was ready and responded with a comprehensive new building plan, and a group of qualified staff in place.

The first state appointed superintendent was Herbert Wooley, who reported the situation as "hopeless". Despite

the construction of a few new buildings and Wooley's numerous efforts to clean things up, he complained that he had inherited

a "medieval pesthouse", and was able to "raise it's standards to the equivalent of a 17th century asylum".

After little less than three years, he resigned. He was replaced by Charles Zeller, previously the superintendent of Fairview

state hospital, who remained through most of the new building construction.

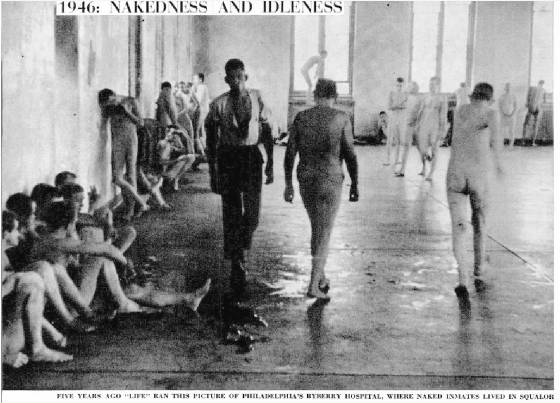

The state hired a new primary architect in 1938, as Johnson had died in 1933. George Wharton Pepper Jr, son of Philadelphia

councilman George Pepper, and grandson of Provost William Pepper, withdrawn from his previous firm Tilden and Pepper, and

opening his own on Walnut street, was clearly the lowest bidder. Pepper's layout, an art-deco building plan was drawn up and

after several changes, was accepted by the board in 1940.

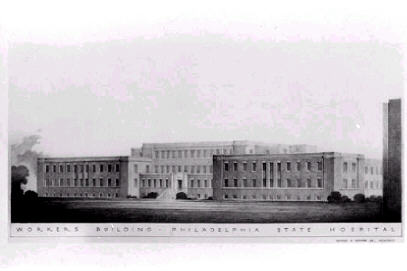

In 1941, at a large ceremony attended by over 500 guests, ground was broken for a new, large and efficient building to

house attendants and most staff, male and female alike. The days of social class favoritism were coming to an end. S-1, or

"Workers' Building", opened in 1942 and housed a gracious new recreational section for patients, which contained

a gym, a bowling alley, a swimming pool, basketball courts, a library and a spa.

| Governor Earle signs over control of Byberry |

|

| Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Record, September 1938, V7:2787/.29 |

In 1938, Byberry's official name was changed to "Philadelphia State Hospital. In 1939, work began on N-6 building, a

huge hotel-like dormitory, and it's twin, N-7. They opened together in 1944. These modern buildings gave the feeling of change

and new ideas, though they would be the last to be erected during the war. By 1945, with the war coming to an end, the state

was expanding the hospital a building a year, holding huge public groundbreaking and dedication ceremonies to show the people

where the money was going. This new building campaign was a showcase of millions of dollars for the public to see. That this

was not the "Byberry Hospital for Mental Diseases" of the past, but the "Philadelphia State Hospital"

of the future.

Unfortunately, the state's bold new plan did little to sway public opinion about byberry. By this time "byberry"

was an unsettling word to most. The photos and stories had been burned into public memory, and no one was too optimistic.

The fact that stories of scandal and abuse continued to litter the newspapers didn't help. The second world war brought the

largest number of returning soldiers in American history, with new and ever more horrific mental problems coming with them.

The military canceled it's contract with byberry to treat returning troops after an examination of the hospital took place

in 1944, and chose to send them to Norristown instead. Nevertheless, the state continued pouring millions into it's new plan.

| N-6 Building and temporary construction office |

|

| Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Record, J. Snyder, April 1944, V7:2786/.56 |

In 1946, a new kitchen and dietary building, N-5 opened. 1947 brought S-1's twin, S-2, a building for working patients. Unfortunately,

the amount of staff the state planned to hire never reached the desired numbers, and the patient/staff ratio reached a despicable

low of 60/4. Working patients picked up a good load of the necessary labor.

By the 1950's S-2 was converted into regular patient dorm space to keep up with overcrowding and its original purpose

was almost forgotten. In 1942, the laundry building for the east group was converted into a gymnasium. In the basement, a

bowling alley was erected for patients. While the state constructed modern, large buildings on the west side of Roosevelt

Boulevard, the battered and decrepit east group still housed most of the male patients.

Once the new buildings were constructed, the state began to makeover the older buildings. In the 1940's the east group

underwent very minor upgrades; new terrazzo tile interiors, new windows, new doors, ect, and continued to house most of the

male patients until the 1960's. The east group had been mostly constructed prior to the advent of many modern building codes.

Their wooden floors for example, having held the weight of so many for so long, began to fail by the late 1930's. Buildings

B, E, F and G were closed down by 1938, and the state chose not to pay much attention to them when they took control of Byberry.

As a result, these four buildings of the east group would actually only serve their purpose for 30 years, being abandoned

longer than they were in use.

The C buildings also got an overhaul between 1944 and 1961, receiving the same basic renovations as the east group. Having

been originally built with concrete floors, the C buildings were much sturdier.

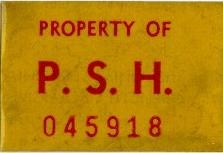

| Decrepit dayroom in C building, 1946 |

|

| Life Magazine, 1951 |

In 1948, ground was broken for the most important building to be built at Byberry, N-3 Active Therapy Building. The state

shared the 2.5 million dollar price tag of the building with the Philadelphia-based Smithkline-French Company, still in the

testing phase of it's wonder drug "thorazine" (chlorpromazine). The building was the first actual step towards aggressively

treating patients who desperately needed it. One half of N-3 consisted of typical patient dormitories and day rooms, but the

other half was filled with modern lab equipment, a staff library, auditorium, and training center, and a new large and efficient

mortuary and autopsy department; all of which byberry had never had before.

With the financial help of Smithkline-French, Philadelphia was able to boast in 1950 that it had the first building in

the state equipped with "modern psychotropic methods and the means to produce them soundly." N-3 Building was also

equipped with an animal testing lab on the roof penthouse for when "more laborious testing" was required. N-3 building

opened its doors in 1950 to a public that assumed the state was in charge of the day to day operations of the new building.

But behind closed doors, it was actually the Smithkline-French doctors who ran the show. The unfortunate aspect of this new

modern care was the countless number of patients who were vigorously tested and watched by eager young chemists who were anxious

to finish testing for thorazine and other psychotropics. Since a consent form required a test subject's signature, some patients

volunteered for testing, others were paid measly sums of money that they couldn't spend anyway, and some were clearly taken

advantage of, incoherent or unaware of what was happening to them.

Byberry by 1949 contained almost 1800 patients that were ward of the state, making them easier test subjects as they had

no family to notify if a fatal reaction occurred. Literally hundreds of patients at byberry died from ailments related to

excessive drug, experimental cosmetics, and skin product testing between 1950 and 1968. But by 1953, Smithkline-French had

perfected thorazine and began producing it and shipping it in large quantities to mental hospitals nationwide.

Thorazine made it possible for patients who were often violent, enraged, and in other cases, vegetative, to function normally

in a matter of hours. This led to the state jumping at the opportunity to relieve some of its overcrowding by releasing these

"cured" patients from byberry, sometimes in a matter of days. Although historically referred to as "progress",

the torturous testing procedures of Smithkline-French and other private companies suffered by patients at byberry is just

another hellish chapter of her history.

| Drawing of new Worker's Building, S-1 |

|

| Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Record, George W. Pepper Jr, Sept.1941, V7:2786/.47 |

In 1949, the same year ground was broken for N-10, architect Pepper died, leaving the layout incomplete. As the building layout

had already been prepared by Pepper, the state contracted out the remaining buildings to various firms, resulting in the strange

yet subtle architectural differences in N-8, N-9, and N-10.

In 1951, a new Tuberculosis hospital was opened. This was the largest building yet, as it contained its own full size

cafeterias and kitchens (TB patients had to be kept secluded from other patients), plus a slew of hospital equipment such

as a new dental office, X-RAY rooms, and an Emergency Room. This was designated N-10 building. Ironically in 1958, medical

science found a "perfected" way of immunizing humans to Teberculosis, and all over the country huge hospitals built

for the care of TB patients were transferred to other uses. N-10 became the medical/surgical building for the campus, having

lived up to its original purpose for under 10 years.

| N-6 and N-7 buildings, circa 1955 |

|

In 1951, the Nurses' and female attendants' quarters (S-10) got it's third and final addition. This new addition made room

for 150 more female employees who chose the option to live on the grounds of the hospital, which now offered an array of medical

training for students. Many went on to work at Byberry or other mental health facilities, state and private.

Byberry was now a modern "institution". The state calculated it's operating costs at approximately fifteen million

dollars a year. Many were concerned that the state did nothing but expand the problem "from a molehill to a mountain",

as would prove correct. For a brief time however, Byberry enjoyed the status of an operational institution. But before long

the overcrowding caught up with byberry again and an even bigger monster was created...

NEXT PAGE

|